Climate and weather

Module 5 of the online permaculture course is all about climate. It’s important because climate helps to refine a design. But how does it do this?

Knowledge of climate can help us:

- choose the correct techniques, e.g. raised beds or beds dug into the soil that can be flooded

- choose the right sort of plants and animals

- choose the right sort of materials to use and whether we want to insulate or build in thermal mass, e.g. greenhouses in cold climates with insulating walls, the amount of ventilation needed in a house.

It is often said that Britain doesn’t have a climate, it has weather. Friends of mine from the centre of France only understood why the British were so interested in the weather when they lived here. In France where they lived, the weather was fairly consistent from day to day and over the seasons. In fact, the weather used to be set for day after day after day whereas here we can have rain, shine, snow and a storm all in one day.

So, what determines climate? There are seven factors which affect climate: Latitude, ocean currents, elevation, topography, near by water, prevailing wind and vegetation.

Latitude

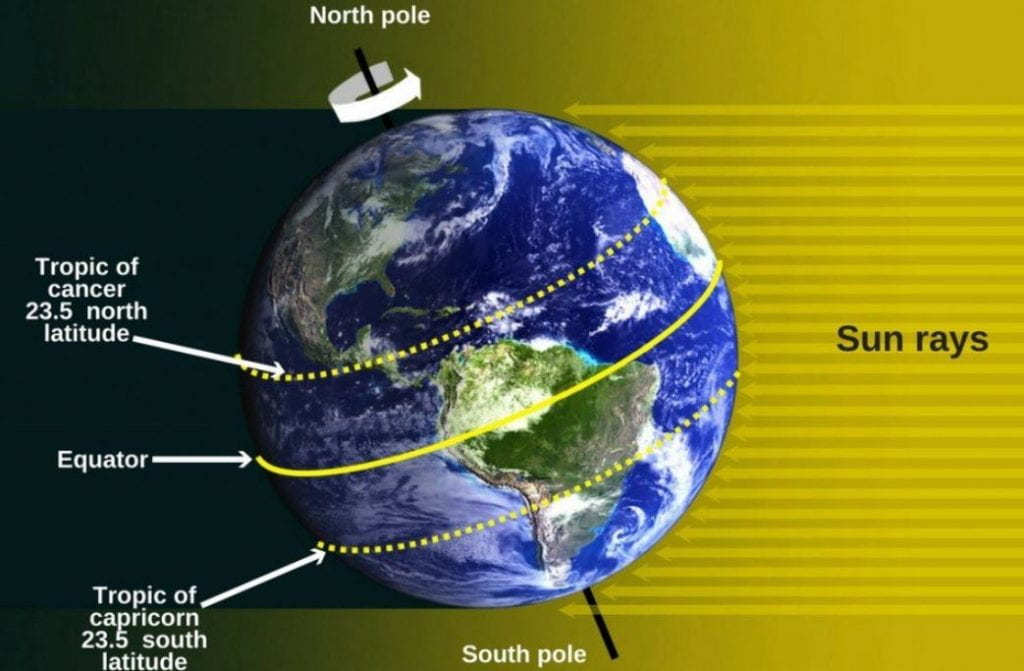

The nearer to the equator the the more sun because the sun hits the equator more directly and in a more concentrated manor. The earth is tilted 23.5 degrees on its axis and this means that for half the year the north is tilted towards the sun and then away from the sun (and vice versa for the south) so the rays hit the earth at a different angle and intensity than they do at the equator. The latitude of the equator is 0° and for the Britain 50° (Cornwall) to 60° (Shetland Isles). Exmouth is 50.6°N.

The nearer to the equator the the more sun because the sun hits the equator more directly and in a more concentrated manor. The earth is tilted 23.5 degrees on its axis and this means that for half the year the north is tilted towards the sun and then away from the sun (and vice versa for the south) so the rays hit the earth at a different angle and intensity than they do at the equator. The latitude of the equator is 0° and for the Britain 50° (Cornwall) to 60° (Shetland Isles). Exmouth is 50.6°N.

Ocean currents

Ocean currents are a very important element for the climate of Britain. As a small island, in comparison with Europe, we are very affected by them. A line drawn from London around the globe would pass through southern Siberia and near Hudson Bay in Canada yet London is much milder in winter. The reason for this is the ocean current, specifically the Gulf Stream which brings warm water from the Caribbean.

Devon has the longest coastline of any region in the UK, having coastline on the north and south of the county.

Elevation

In general, for every 100m that you go up, the temperature drops by 1°. Air is less dense at altitude, the molecules are more dispersed than at sea level. As a result of this the molecules do not bump into each other so much and therefore produce less heat. In Exmouth we are at sea level so there is no reduction in the temperature due altitude.

Topography

Topography is how the geography of the place affects the weather and ultimately the climate. Hills or mountains can create rain and the weather can be different on the windward or leeward side. There can be a funneling of winds due to the shape of the land and a large body of water such as a lake or reservoir can also create milder temperatures.

Topography is how the geography of the place affects the weather and ultimately the climate. Hills or mountains can create rain and the weather can be different on the windward or leeward side. There can be a funneling of winds due to the shape of the land and a large body of water such as a lake or reservoir can also create milder temperatures.

The west of the UK is higher than the east through plate movements many, many years ago. The prevailing winds are south westerly and this means that there is a lot more rain in the west compared with the east. However, Exmouth is in the rain shadow of Dartmoor as evidenced by the comparison rainfall chart for Princetown on Dartmoor , windward side of the moor and Exmouth (leeward side of the moor). Our rainfall is about half or less of that in Princetown.

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | |

| Princetown in mm | 219 | 169 | 162 | 109 | 120 | 116 | 112 | 133 | 156 |

| Exmouth in mm | 88 | 69 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 61 | 59 | 67 | 60 |

We are in a temperate climate with cool, wet winters and warm, wet summers but that is not the same for the whole country. The south east is cold and dry in the winter and warm and dry in the summer. The north west has mild winters and cool summers with heavy rain all year round and the north east has cold winters and warm summers with steady rain all year.

The nearest place to Exmouth with a different climate is Gran Canaria which has a sub tropical climate with hot summers and mild winters and is a place many people from the UK visit in the winter.

The nearest place to Exmouth with a different climate is Gran Canaria which has a sub tropical climate with hot summers and mild winters and is a place many people from the UK visit in the winter.

The Koppen-Geiger Classification

This is a climate classification system based on the vegetation that grows in a place because plants depend on temperature and precipitation to grow. There are 5 climates – A. tropical, B. Dry, C. Temperate, D. Continental and E. Polar. These are then divided into sub-categories according to level of precipitation and then the level of heat. The UK is Cfb which is temperate (or ocean), the f stands for no dry season and the b is the temperature of each of four warmest months 10 °C or above but warmest month less than 22 °C. Using maps based on this system from 1901 to 2010 it can be seen that there is an increase in aridity across the world and a decrease in polar regions.

The USDA hardiness zones are used world wide to denote the type of plants that will grow in that region. Most of the UK is zone 8 but here in Exmouth we are in zone 9 meaning that the lowest average temperature is -6.7°C.

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) has its own hardiness classification but applies it to plants rather than locations. It works on the theory that we all have microclimates in our gardens and therefore can place a wider range of plants than one overall rate of hardiness might suggest.

Because my patch of land is right by the sea, flow has had a very obvious impact on it, creating the dunes in the first place but wind, water and people continue to shape it. It starts at the eastern end at the entrance/exit to a temporary car park which is necessary for the influx of visitors in the summer. The beach, however, is the other side of the road so most people that come out of the carpark need to cross the road and the quickest way to do so is walk up the patch of land to get to the edge of the road. These shortcuts,

Because my patch of land is right by the sea, flow has had a very obvious impact on it, creating the dunes in the first place but wind, water and people continue to shape it. It starts at the eastern end at the entrance/exit to a temporary car park which is necessary for the influx of visitors in the summer. The beach, however, is the other side of the road so most people that come out of the carpark need to cross the road and the quickest way to do so is walk up the patch of land to get to the edge of the road. These shortcuts,  It would be quite possible to build a set of steps here that flare out at the bottom, mirroring the erosion but would what happened in this picture happen because we know it is just quicker to walk up. Actually, in this instance I would formalise that path as well so that people have a choice about which to use.

It would be quite possible to build a set of steps here that flare out at the bottom, mirroring the erosion but would what happened in this picture happen because we know it is just quicker to walk up. Actually, in this instance I would formalise that path as well so that people have a choice about which to use. I have talked about the wind and the impact it has on this patch of land and some of its edges before but this patch has one difficult, solid edge where a wall and pavement meet. In a southerly blow, the sand hits the wall and drops to the base where one of the road sweepers that keep the beach area looking neat and tidy sweeps up the sand and puts it in his cart to empty it else where I am presuming. I have often wondered what would happen if they didn’t. Would that paved area fill up eventually and join up with the dune/land at the same level?

I have talked about the wind and the impact it has on this patch of land and some of its edges before but this patch has one difficult, solid edge where a wall and pavement meet. In a southerly blow, the sand hits the wall and drops to the base where one of the road sweepers that keep the beach area looking neat and tidy sweeps up the sand and puts it in his cart to empty it else where I am presuming. I have often wondered what would happen if they didn’t. Would that paved area fill up eventually and join up with the dune/land at the same level?

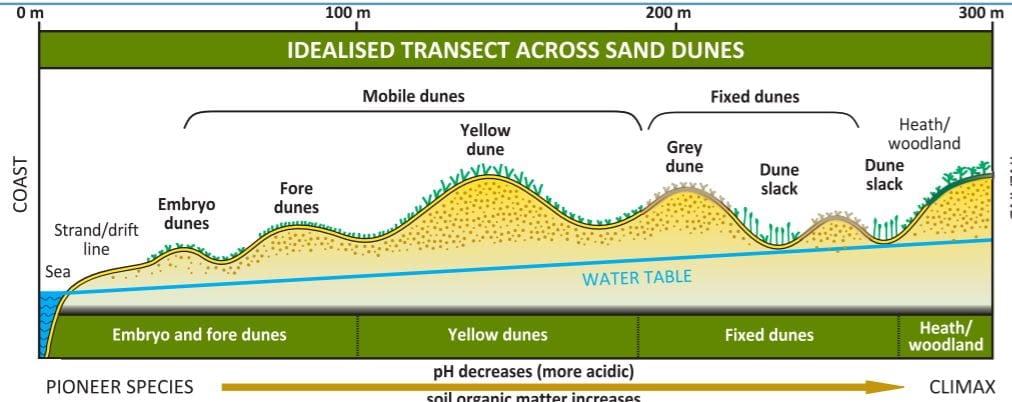

In order for sand dunes to be made, you need two media, sand and wind, where the wind blows sand, deposits it and then blows it away again. In geographic terms, deposition and erosion. Whilst the dunes behind the beach are quite stable, this piece of land has mini dunes on it. The wind blows the sand which gets trapped by the grass on the land and is then eventually blown off, hitting the wall opposite it and deposited at the base of the wall. The ripples in the sand come from the patterns on the base of trainers rather than anything nature has created. Although hard to see, the pattern is again a wave pattern.

In order for sand dunes to be made, you need two media, sand and wind, where the wind blows sand, deposits it and then blows it away again. In geographic terms, deposition and erosion. Whilst the dunes behind the beach are quite stable, this piece of land has mini dunes on it. The wind blows the sand which gets trapped by the grass on the land and is then eventually blown off, hitting the wall opposite it and deposited at the base of the wall. The ripples in the sand come from the patterns on the base of trainers rather than anything nature has created. Although hard to see, the pattern is again a wave pattern.

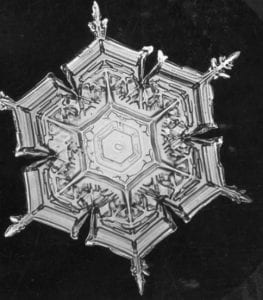

In nature there are a limited number of patterns but an infinite number of variations. Take a snowflake: there are no two snowflakes that are the same although they are all formed in a similar way.

In nature there are a limited number of patterns but an infinite number of variations. Take a snowflake: there are no two snowflakes that are the same although they are all formed in a similar way.

This explosion, however, is the dried flower of Allium x ‘Globemaster’ with some seeds left in the seedheads. The flowerhead is made up of hundreds of little flowers in a beautiful purple during late May early June. It is an excellent example of a pattern within a pattern within a pattern because it is an explosion making a sphere with some branching at the end of each individual flowerhead. You get a really clear picture of how the seeds are dispersed all around the plant, some near and some slightly further away.

This explosion, however, is the dried flower of Allium x ‘Globemaster’ with some seeds left in the seedheads. The flowerhead is made up of hundreds of little flowers in a beautiful purple during late May early June. It is an excellent example of a pattern within a pattern within a pattern because it is an explosion making a sphere with some branching at the end of each individual flowerhead. You get a really clear picture of how the seeds are dispersed all around the plant, some near and some slightly further away.

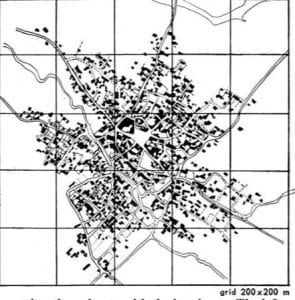

So, how can we use this pattern in design? This is an image of La Ferme du Bec Hellouin in Normandy, France. Below the polytunnels can clearly be seen an exploding pattern set of beds all coming off a central point. Often in walled gardens there would be a well or water store in the centre of this type of pattern, making it quicker and easier to water the beds – or nowadays a tap on a standpipe from a gravity-fed reservoir on higher land.

So, how can we use this pattern in design? This is an image of La Ferme du Bec Hellouin in Normandy, France. Below the polytunnels can clearly be seen an exploding pattern set of beds all coming off a central point. Often in walled gardens there would be a well or water store in the centre of this type of pattern, making it quicker and easier to water the beds – or nowadays a tap on a standpipe from a gravity-fed reservoir on higher land.

A vortex is a spiral where the air or water swirls around and anything caught in the motion is pulled into the centre. One place where this can be used in the garden is in free flow water features to aerate the water. They are based on an idea from Rudolf Steiner and shown through

A vortex is a spiral where the air or water swirls around and anything caught in the motion is pulled into the centre. One place where this can be used in the garden is in free flow water features to aerate the water. They are based on an idea from Rudolf Steiner and shown through  A book I have bought to read as a result of this module on patterns in nature is

A book I have bought to read as a result of this module on patterns in nature is

It is still behind the buildings but at the edge and probably is just not protected enough.

It is still behind the buildings but at the edge and probably is just not protected enough.