Planning a plant guild

The use of guilds in permaculture is about many things. Firstly, it is a group of plants that work together to provide the conditions that they all need to survive. This is more than being companion planting because the sum of the group is greater than the individual parts. Secondly, they are an ideal bridge between a vegetable garden and a wildlife garden, perfect for my aim which is to demonstrate that wildlife and vegetable growing can go hand in hand.

The use of guilds in permaculture is about many things. Firstly, it is a group of plants that work together to provide the conditions that they all need to survive. This is more than being companion planting because the sum of the group is greater than the individual parts. Secondly, they are an ideal bridge between a vegetable garden and a wildlife garden, perfect for my aim which is to demonstrate that wildlife and vegetable growing can go hand in hand.

Perhaps the most famous guild is the Native American of corn, squash and climbing beans. Besides providing food, corn provides a stalk for the beans to climb, the beans provide nitrogen for the corn and help to provide a complete dietary protein when eaten with the corn. The squash sprawls along the ground providing a living mulch and food rich in calories, beta carotene and zinc. I have tried to grow these ‘Three Sisters’ together a couple of times and whilst the corn and squash seem to do OK, I could never manage the beans – I suspect it is a matter of timing of the bean transplants.

Several articles and books I have read recently say that there is a fourth plant included in this guild – cleome – a rather lovely annual flower that acts as a squash beetle trap, amongst other things, in America. To my knowledge, we don’t have that beetle here in the UK. Other cultures have used Amaranth as the fourth plant in this guild.

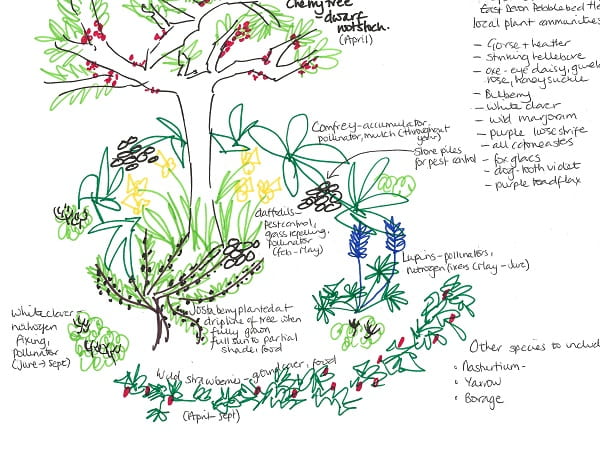

The cherry tree guild I will plant in autumn and spring.

Click here cherry tree guild if the image is not clear.

Guilds usually start with something you want – a cherry tree – and gradually connections are added consisting of other plants to provide protection, nurse it through its young life, cover and build the soil, provide shelter and repel pests. Once the tree has established itself, climbing plants can also be used to add to the vertical growth. Plants that flower throughout the year will be needed but particularly those that attract pollinators when the tree flowers. Pest predators can be encouraged through the use of log or stone piles – stones are something we have a lot of! Our role once planted is to observe and take note of what works.

Toby Hemenway in his book Gaia’s Garden offers several questions which can help us decide what works and what doesn’t.

- What is the dominant species of the community? Is it useful for humans – food, beauty, animal feed or other benefit? Is a related plant even more useful?

- Which plants are offering food to wildlife? What wildlife uses them? Are these animals desirable in the garden?

- Are any plants capable of providing food for humans? Do any of these plants have domesticated relatives that can provide fruits, tubers, seeds, nuts, herbs or greens?

- Which species are common to more than one community? These may be able to connect a guild to another part of the garden.

- Does any species show exceptional pest damage or have harmful numbers of insects living on it? This might not be a desirable variety?

- What species generates most of the leaf litter? Have you got enough? Does it make a good mulch plant?

- How well does the community withstand drought or a lot of rain?

- Do any of the plants have bare ground around them or stunted growth? This may be due to deep shade but might also be an allelopathic plant (inhibition of one plant by another).

- Are any plant families heavily represented? If so, domesticated varieties could be substituted.

- Does the community contain any nitrogen fixers? These are probably critical members. Are there enough?

If you would like to read more about guilds, here are some articles to try:

Permaculture Research Institute: Guilds for the small scale home garden by Jonathon Engels including a guild for growing tomatoes.

Permaculture Design: Vegetable and Herb Guilds by Paul Alfrey with another guild for tomatoes!

The cherry tree guild and natural pest control from Tenth Acre Farm just in case you think I am obsessed with tomatoes!

How to build a permaculture fruit tree guild from Tenth Acre Farm with an apple tree as an example.

What do you plant around your fruit trees?

I have lived in my present house for 20 years now. When we first moved in there was a pretty white flower that was tucked around the edges of the garden in shady parts. I left it for about three years until one day I realised that it was all over garden and had spread incredibly. In fact, it was taking over.

I have lived in my present house for 20 years now. When we first moved in there was a pretty white flower that was tucked around the edges of the garden in shady parts. I left it for about three years until one day I realised that it was all over garden and had spread incredibly. In fact, it was taking over. I recently read

I recently read  Phase 2 – Site assessment

Phase 2 – Site assessment The plant has both male and female parts and so you only need one! The bulbs produced are deposited on the soil where the roots pull them underground, deeper and deeper. The seed can be dispersed by wind and sometimes by ants. I must admit to not having noticed seeds so will look for those next year.

The plant has both male and female parts and so you only need one! The bulbs produced are deposited on the soil where the roots pull them underground, deeper and deeper. The seed can be dispersed by wind and sometimes by ants. I must admit to not having noticed seeds so will look for those next year.