Changing my mind about ragwort

Cinnabar moth July 21

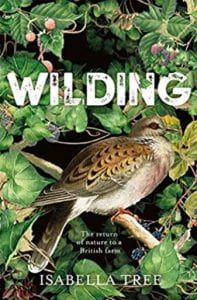

I have always pulled ragwort up off my allotment but reading Wilding by Isabella Tree made me think about what I do. What stopped me in my tracts was the fact that 177 species of insect use common ragwort as a source of nectar or pollen. That’s quite a lot on a small plot!

Seven species of beetle, twelve species of flies, one macromoth – the cinnabar, with its distinctive black-red-and-yellow rugby jersey caterpillars – and seven micromoths feed exclusively on common ragwort. It is a major source of nectar for at least thirty species of solitary bees, eighteen species of solitary wasps and fifty insect parasites. (Tree, 2018, p142)

I know ragwort can be toxic to horses especially and cattle but apparently they only eat it if they are in an over-grazed field where there is not enough grass for them. There are other plants that can have the same toxic effect on them: foxgloves, elder, spindle and daffodil all of which I have on the plot (although I have no horses or cattle!) and no one bats an eyelid about them.

The seed can stay dormant in the soil for about 10 years and only needs a slight scratching around it to stimulate germination which would explain how I come to have it each year on my plot and the wildlife plot. This year, however, I am going to let it grow on the wildlife plot.

And if you want more information about micromoths, this site is useful.

A volunteer who works with me on the wildlife plot suggested I read

A volunteer who works with me on the wildlife plot suggested I read