Managing water on the allotment – part1

Winter is a quieter time on the allotment in terms of sowing and planting but not in terms of planning. After a couple of hot summers I know that I do not collect enough water when it does rain. I have 4 water butts on my polytunnel, one at each corner and one water butt behind my shed and can empty these in about two weeks if it is very hot. Water butts are not the only way of saving water and I can’t have the plots covered in blue butts so need to think about other ways of too.

This is the first in a series of posts about water management on my allotments.

I like the permaculture phrase about water of slow it, spread it and sink it as it rains with this being the number one way of managing water. The cheapest method of storing water is to store it in the ground. The secondary aim is to capture as much water as is reasonable to use during dry periods. How you use these strategies completely depends on the site.

Things to think about are:

- How and when does your water fall? Is it consistent throughout the year, during the winter or from large summer storms?

- How does water move across your plot? Does it sit anywhere during rainfall? Do you have slopes on your site?

- What type of soil do you have? This will affect how much soaks in and how much runs off. A sandy soil has a lot less run off than a water-logged clay soil.

We also need to consider all the ways in which we can sink, slow and spread water across the allotments. The following are a list of things we could do – some may not be appropriate but at this stage I don’t want to rule anything out.

- Swales. These work best on a slope of 5% or less where a trench following the contour of the land is dug out and the soil piled up on the downhill side to make a raised edge or berm to hold water back. They don’t work particularly well on small watersheds, sandy soil and forested areas as there won’t be much run off. If you are still not sure about them, the video below explains them clearly.

- Hugelkultur. This is a bed built out of waste woody material, and other things, that is drier on top and wetter lower down the slope. I built one of these in my garden last spring and it definitely does not need as much watering as well-mulched beds built on the flat. I watered those at least once a week throughout the dry spring and summer but only watered the hugelkultur bed twice during the whole season.

- Stones. Sepp Holzer uses stones, probably more like rocks, to provide microclimates on his farm. They reflect the sun and enable him to grow crops that wouldn’t normally grow up in the mountains in Austria, such as lemons, but also keep the soil moist underneath and around them. It is true that if you turn over a stone/brick on the plot it is usually damper underneath. The downside is that you can also find slugs and snails there too.

- Ollas. These are unglazed pots sunk into the soil near the roots of plants that are filled with water. Because they are unglazed, they gradually release the water or actually, the plant pulls the water from the pot and grows around it. An olla has an opening at the top which is slightly proud of the soil where the water can be topped up. This short video shows a container being planted up with an olla or as we might know it, a terracotta plant pot. All it needs is a lid on top and the bottom hole sealed up.

How do you store water in your soil so that you can make the most of this resource?

Useful resources

- Gaia’s Garden by Toby Hemenway: Chp5 is an excellent overview of water and how it can be managed.

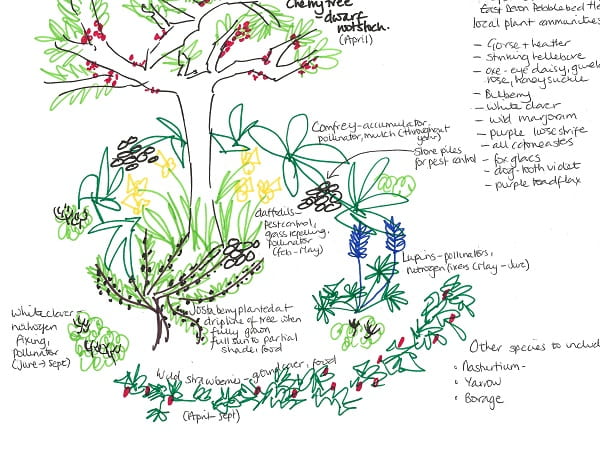

The use of guilds in permaculture is about many things. Firstly, it is a group of plants that work together to provide the conditions that they all need to survive. This is more than being companion planting because the sum of the group is greater than the individual parts. Secondly, they are an ideal bridge between a vegetable garden and a wildlife garden, perfect for my aim which is to demonstrate that wildlife and vegetable growing can go hand in hand.

The use of guilds in permaculture is about many things. Firstly, it is a group of plants that work together to provide the conditions that they all need to survive. This is more than being companion planting because the sum of the group is greater than the individual parts. Secondly, they are an ideal bridge between a vegetable garden and a wildlife garden, perfect for my aim which is to demonstrate that wildlife and vegetable growing can go hand in hand.